Optimism and Humility

The delivery of software products is complex. All manner of challenges can (and regularly do) catch experienced practitioners out. As a result, product features are often delivered late, over budget, and with reduced scope, leaving clients disappointed. One reason for this, I argue, is that experienced practitioners can convince themselves that they have seen similar work before and can therefore envision a path to success. This innate optimism bias, coupled with deadline and cost pressure from management and/or clients often leads to unrealistic delivery targets (Jørgensen and Grimstad, 2005). Furthermore, this same optimism bias can blind practitioners from seeing the true complexity of a delivery and, in turn, prevent them seeking help or guidance. In this post I argue that humility in the face of the seemingly benign can contribute to better outcomes.

Optimism Bias

Optimism bias in human beings is a well-documented phenomenon (1, 2, 3), it is no surprise then that it arises frequently in software product development. Fred Brooks in his excellent book The Mythical Man Month1 describes an optimism bias mechanism in the context of software development:

“Computer programming, however, creates with an exceedingly tractable medium. The programmer builds from pure thought-stuff: concepts and very flexible representations thereof. Because the medium is tractable, we expect few difficulties in implementation, hence our pervasive optimism. Because our ideas are faulty, we have bugs; hence our optimism is unjustified.” (Brooks, 1975)1

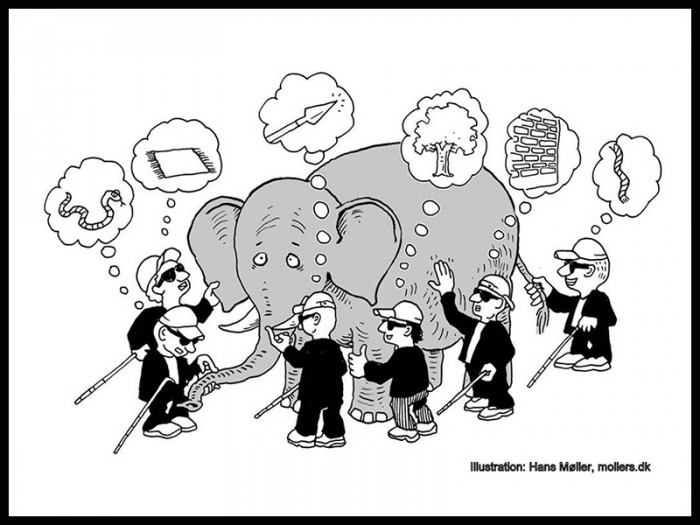

Extending Brooks’ idea beyond a single ‘programmer’ to the modern multi-disciplined ‘feature team’ additional “thought-stuff bugs” may also arise through miss-matching mental models. Building consensus is hard, and communication overhead (i.e., the complexity of squashing any “thought-bugs”) increases as teams get bigger. All of this suggests that even after 45 years of progress in the industry, optimism bias is alive and kicking in modern organisations.

Humility

If optimism bias arises from differences in our collective mental models of what is happening and how it will progress, then humility could help us uncover tools and techniques that can help align these models within a delivery team.

In order to address optimism bias, we must first acknowledge its existence, this requires constant attention to how you are thinking and an empathetic approach to determining how others might think. This attention can help identify times when over optimism is creeping in:

“The next release will solve the problem …“

“Once we complete this feature we will be back on track …“

“No-one has said they cannot deliver, so the delivery must be proceeding according to plan …“

Finding mechanisms to catch overly optimistic thinking and challenging its assumptions can be an effective safeguard. Additionally, retrospective ceremonies built into ‘Agile’ teams can create the space to discuss situations where a team has been caught out by over-optimism and adapt their estimation techniques or delivery process accordingly. For a Product Owner this could involve finding better questions to ask to ‘flush-out’ hidden delivery risks or alternative solution configurations with both development teams and clients.

Finding a better way

Becoming aware of optimism bias and asking better questions is a great start, however I believe there is room to do more. A second form of the optimism trap is to see the current product and delivery that is being worked on as unique or special in some way. Whilst this is partly true as we are working with the “thought-stuff” of every changing teams and stakeholders, this type of thinking can prevent us from using tried and tested techniques to build consensus and improve our practice.

It is very common in today’s organisations to see developers on stackoverflow and reading text books on development languages, project managers regularly refer to manuals such as Prince2, yet, in my experience, Business Analysts and Product Owners often devise and develop their own new approaches to building consensus and specifying work afresh for each delivery.

Whilst all software deliveries are unique (by virtue of the people involved if nothing else), there is enough commonality between them that standard tools and techniques can be effectively used. Just as a developer uses a third-party library, product owners can use templates, diagram-formats and questioning techniques informed by industry-tested best practice to build the foundations of their daily working practices. Doing so can help save brainpower for the truly challenging and novel aspects of any problem.

Where to find help

Next time you find yourself having to lead a workshop, write a user-story, prepare a document, for a seemingly benign deliverable, be humble enough to think “Someone has done this before”. Two minutes of searching on the web yields a template, a guide, some advice, an example, and although some of these are not always useful, seeking an external view on how to approach the problem can:

- help to validate your own thinking,

- help to sell your approach to others. “I’m using a best-practice technique from blah” can be a compelling argument.

Specific examples

One book I repeatedly return to is Software Requirements (Wiegers and Beaty, 2013)2. This book provides diagrams, document templates and guides to grammar to use to help engineer software requirements. The International Institute of Business Analysts (IIBA) publish a “Business Analysis Book of Knowledge” - (BABOK) containing a codification of practice for BA/PO work, and consultancies like Construx provide free (and paid for…) resources on tried and tested approaches. Familiarity with this type of material that is being generated in the industry can help a BA/PO craft a better approach. And, better yet, consistent use of effective tools can help to build your personal brand and can be shared with colleagues.

So What?

Using a humble approach can help us integrate the views of all stakeholders, leverage best practice. Doing so can help to address innate optimism bias in product development which should deliver better outcomes for clients.